Stories

Tackling Canada’s Opioid Epidemic Includes Addressing the Chronic Pain Crisis

BY NEIL FRASER AND PETER TOMASHEWSKI While the national opioid epidemic is killing thousands of Canadians each year1— straining an already overburdened healthcare system — there is another,...

BY NEIL FRASER AND PETER TOMASHEWSKI

While the national opioid epidemic is killing thousands of Canadians each year1— straining an already overburdened healthcare system — there is another, related health crisis of pandemic proportions affecting millions of Canadians: chronic pain.

Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts for three months or longer.2 It can occur anywhere in the body and can range from mild feelings of discomfort or aching to completely debilitating pain. While most common in older adults, it can impact anyone. Symptoms include shooting pain, burning or aching, or recurring feelings of soreness, tightness and stiffness. It can be challenging to diagnose and equally challenging to treat.

The toll of chronic pain on individual Canadians, families, and our country is staggering. According to the Canadian Pain Society, one in five Canadians lives with chronic pain and it costs our healthcare and social systems billions of dollars per year.3

For many, this constant physical burden is devastating to their quality of life. In extreme cases, it can lead to a vicious cycle that starts with an inability to work or be productive, and damaged relationships with loved ones. This can lead to depression, which is exacerbated by a lack of treatment. The vicious cycle can end with drug addiction — contributing to the opioid crisis and avoidable overdose deaths — or suicide.4

The reliance and misuse of opioids is inextricably linked to chronic pain. We need a more comprehensive pain management strategy if we are to chip away at the crisis before us.

A multidisciplinary approach would involve the right professional support and the right treatment for the right patient at the right time, including the use, where appropriate, of physiotherapists, physiatrists, and other specialists who focus on physical medicine; surgeons who might be able to treat the underlying cause of the pain and anaesthetists; and psychologists and psychiatrists who may become necessary once the pain is memorized by the central nervous system.

Chronic pain sufferers who fail to get relief from opioids or surgery are sometimes told that the pain is all in their head. While this is meant to suggest it’s imaginary, it demonstrates a complete lack of compassion for, and understanding of the complexity of pain. In 2013, Uta Sboto-Frankenstein and her colleagues in Winnipeg showed that you can visualize pain signals in the brain using an MRI,5 proving that pain is both real and quite literally in your head.

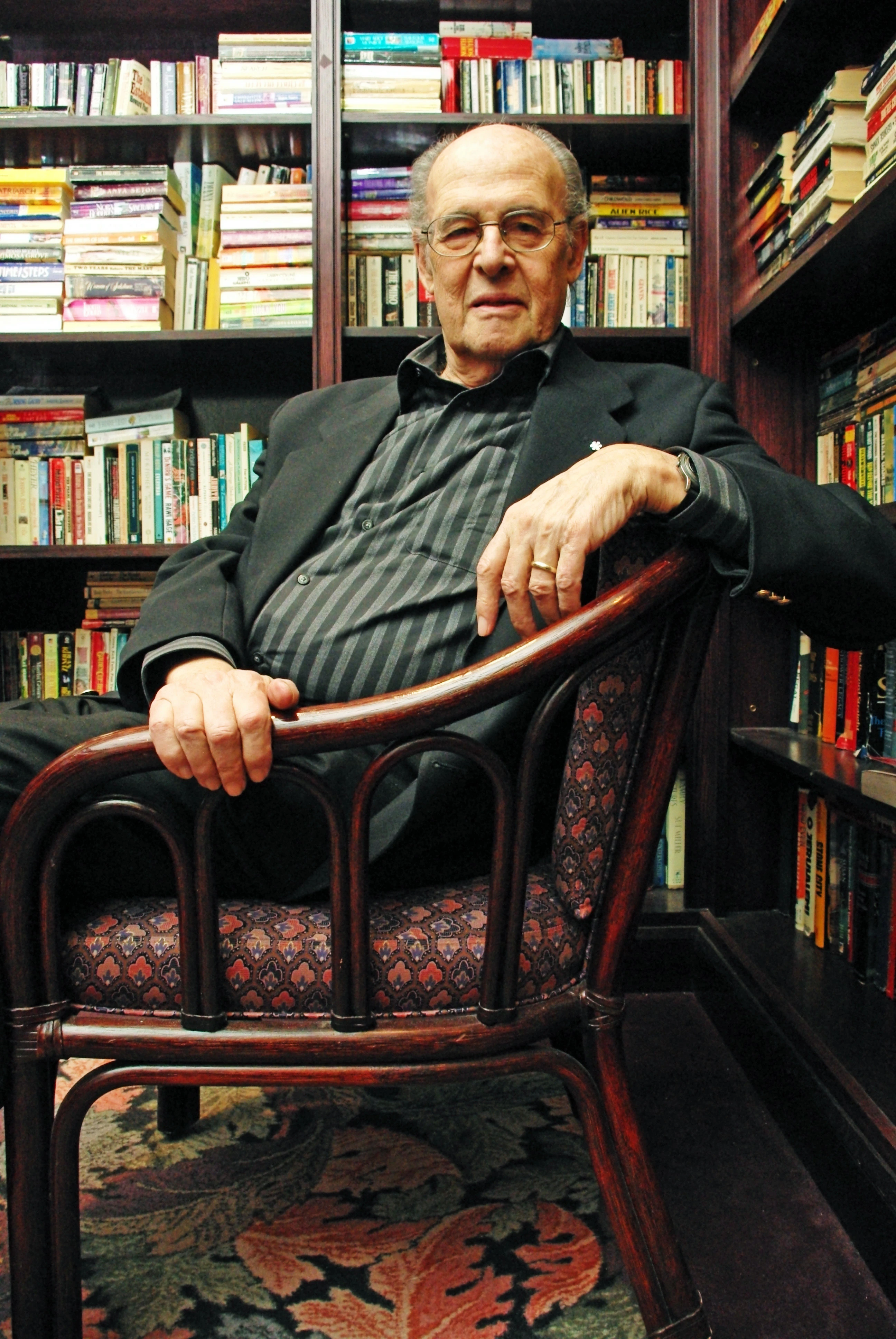

In the 1960s, Canadians Ronald Melzak and Patrick Wall from McGill University developed the gate control theory of pain, which explains the physiology of pain, previously associated with psychology. Melzak later theorized that if you prevent the pain signal from travelling to the central nervous system, you can relieve the sensation of pain.

That theory was put into practice with the development of various electrical stimulation devices, including spinal cord stimulation, first used in 1967,6 and TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) machines, launched in 1974.7

A former skater from Brantford, Ontario, 8 Sarah Graff lived with debilitating pain in her back and legs for more than 10 years. The mother of two young children turned to pain medications and spinal blocks (spinal anesthesia), but the pain was still so intense that it remained difficult for her to enjoy a normal life.

She was eventually referred to the Neuromodulation Program at Hamilton Health Sciences where she was implanted with a spinal cord stimulator (SCS), a pacemaker sized device which delivers mild electrical pulses to interrupt pain signals before they reach the brain. The results were immediate. Pain that had dominated her world for more than a decade was gone. Sarah now credits this pain management therapy with an increase in her quality of life.

Sarah was fortunate. She was one of approximately 4% of eligible candidates in Canada to get access to SCS, despite a large body of evidence of its effectiveness and decades of availability. By comparison, access in Western Europe and the United States is estimated at 21%.8

It’s the many stories like Sarah’s, and the clinical evidence showing the efficacy of SCS,8 that highlight how a multi-disciplinary approach, including access to proven technologies, can help address Canada’s chronic pain crisis and help reduce the deadly impact of the opioid epidemic. Together with other measures, such as increasing pain education among the medical community, and focusing on early interventions, we can break the debilitating cycle of chronic pain.

The good news is that best practices already exist and can be adopted across the country. Although specific to back pain, several provinces have already begun implementing Inter-professional Spine Assessment and Education Clinics, first launched by Dr. Raja Rampersaud from Toronto Western Hospital in 2012. Pain BC9 is an online portal that provides support and access to resources for chronic pain sufferers in the province, and St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver has one of the most comprehensive multi-disciplinary teams focusing on complex pain, similar to the approach of the world-renowned Mayo Clinic.

Pain management therapies such as the ones Medtronic develops are not the complete answer to ending chronic pain or the opioid epidemic. Our device-delivered therapies don’t treat opioid addiction. But they can provide patients with alternatives to relieve pain and reduce exposure to high-dose opioids and long-term systemic opioid use that could lead to misuse and addiction.

Medtronic is committed to partnering with health system stakeholders to disrupt the opioid epidemic by providing solutions for improved pain management. We are working to increase awareness of the benefits of long-term, proven pain management solutions among patients, healthcare providers, payers, regulators, patient advocacy groups, and government decision-makers — solutions that can reduce or even eliminate the need for opioids.

No single entity can solve Canada’s opioid and pain crises alone. We need to consider all options and show compassion for chronic pain patients — together.